Cool data sets for climate protection

Ida Hausmann's award-winning Master's thesis in Geomatics focused on the vital phytoplankton off the Californian coast. We spoke to her about her academic career and her motivation for working with environmentally relevant data sets.

HKA: You have completed a Master's degree in Geomatics. What do you learn there?

Ida Hausmann (IH): Many people may have an idea of what "geodata" is. This is data that is collected in a variety of ways and has some form of spatial reference. In our Geomatics degree program, we work with this data in every conceivable way. We have many different specializations, from data science to remote sensing or satellite image analysis, to the visualization of this data. Even if you come from geodesy, surveying, which looks at the mathematical aspect behind it, we are really very broadly positioned. In summary, it's applied computer science, so we do a lot of programming and always have an environmental and spatial aspect to it. It's an international degree course, which means that students from all over the world come together and the lectures, exams and final thesis are in English. I was really scared because I don't actually speak English very well, but that wasn't a problem at all. Our professors aren't native English speakers either - they found a way for everyone. The ones who were really good at English helped us weaker ones. Interculturally, this mix was really cool. There were students from very different countries: France, Bangladesh, America, Colombia, South Africa - very international.

What were the differences between the models?

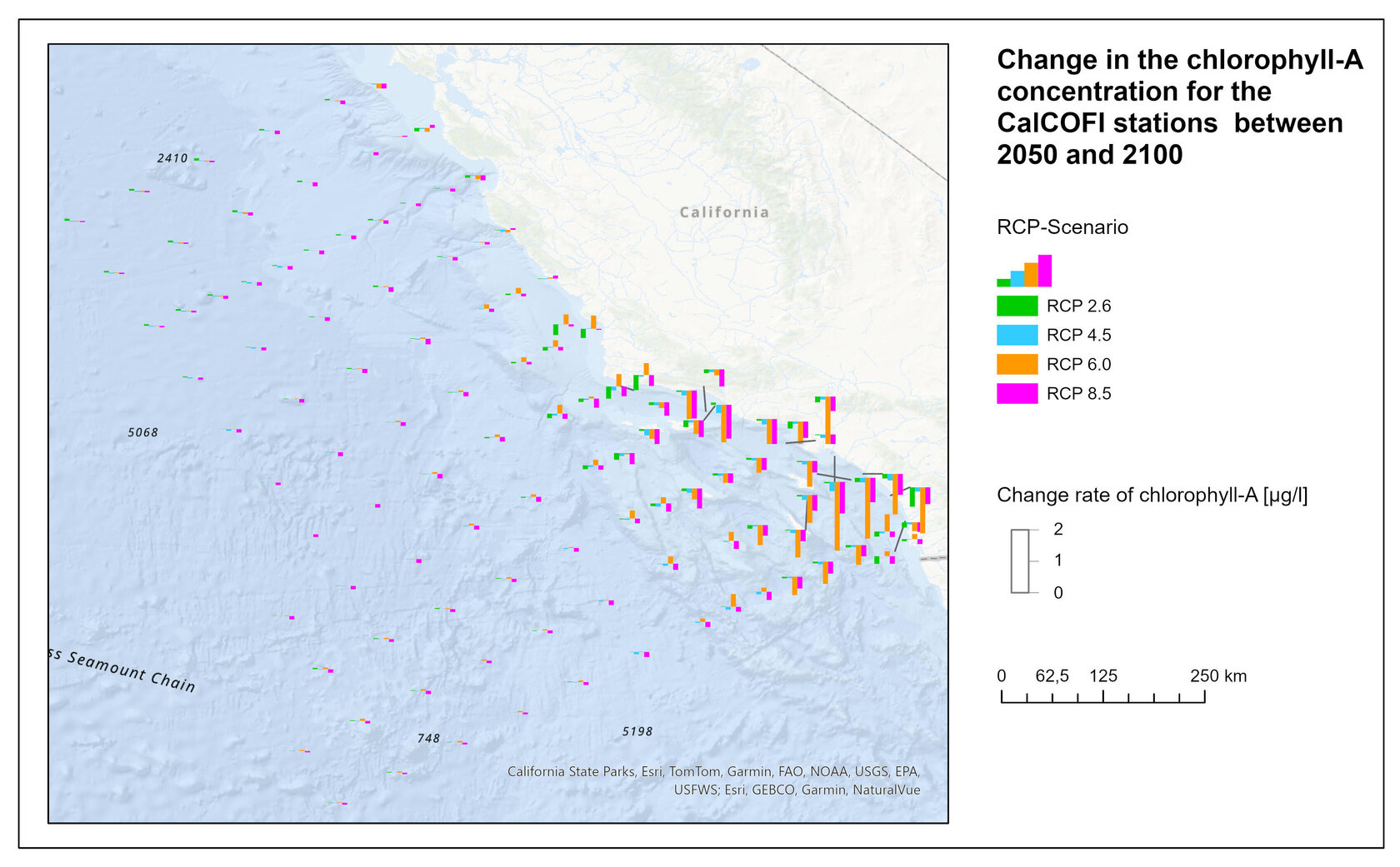

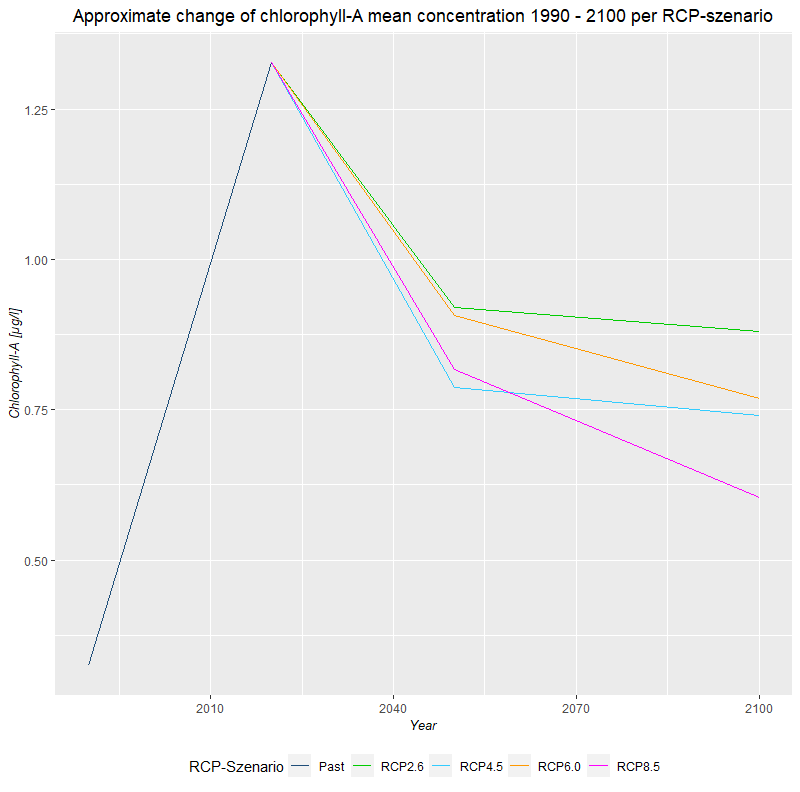

IH: Ultimately, you can basically say that no matter what happens, the phytoplankton will be reduced in the area of the Californian coast in the long term. We've also heard a lot in the media that an algae bloom (toxic algae bloom) took place in 2025 and is still taking place to some extent, and too much is not good either. But no matter how we develop, phytoplankton will decrease overall. If temperatures continue to rise very sharply, we will lose significantly more phytoplankton - this can already be clearly seen in the results that strong climate change will lead to even less phytoplankton. In the desirable scenarios, where CO₂ emissions could even be reduced, the phytoplankton will level off in a range that was often seen in the past, so the dependence on the CO₂ concentration could be shown.

IH: The data is based on two different sources. I trained a model on historical data that was collected by CalCOFI; this is actually a really cool data set, they have been using ships to sail to different measuring stations every quarter since 1940, take water samples and then measure a lot of parameters in order to really create a time series data set that you can do a lot with. That was my basis for finding out which environmental parameters have what influence on my phytoplankton.

I used data sets from Bio-ORACLE for the prediction. These are really cool data sets that cover the entire globe. A lot of very complex climate models are currently being calculated, so you can pull out all kinds of different parameters. And this data set combines different climate models - they all differ a bit from each other - and it takes the average of them, so to speak, so that it is a very robust data basis because it takes a lot into account. I then looked at what was predicted for the water temperature, for example, and was then able to enter that into my model so that it could tell me: If the water temperature gets this high, then our phytoplankton will be like this.

How did you go about dealing with difficulties in your work?

IH: Professor Dr. Christine Preisach was my first supervisor and it was with her that I came up with the topic. I didn't have to fly to California; the data sets are freely accessible and anyone can look at them. I only used a small selection of them.

I think my biggest difficulty was that I wasn't a marine biologist. In order to make a meaningful statement about the relationships between these parameters, I can't just calculate any correlations using data science, I also have to think about it logically: Is this now a variable that really serves me for prediction? For example: I also get the value for oxygen in the data set, but the oxygen content is influenced by phytoplankton, which means that the oxygen content does not help me predict anything, because it is a result. I had to think a lot about things like that, in the end that was the biggest difficulty, reading into it in such a way that it simply makes technical sense; I can't just blindly take data and train some model.

So you've also become a bit of an expert on phytoplankton, so to speak?

IH: I have at least broadened my interest - not directly in phytoplankton, but in the oceans.

How did you get from school to your award-winning thesis?

IH: I slipped out of school with a below-average A-level. I was studying geography and wanted to do something in that field. I roughly researched what was available in Karlsruhe. The KIT quickly popped up and in the end I started studying meteorology there because I found the subject of climate exciting. In the first week, I realized that I had to do a basic physics course, so I quickly grasped the problem for myself, including the way work is done at KIT and what is expected of the students. I wasn't ready for that at the time. In the meantime, I would say: I can now work scientifically. I couldn't at the time, I had to learn it first. That's why I decided relatively quickly: I'd find something else. Because I wanted to stay in Karlsruhe, I thought: Okay, university, that's more applied. My mother was also at a university and told me that it's more academic, you're in smaller groups, you get better supervision and you're not one of 2,000 people.

I applied for both the geodesy course and the environmental and geoinformation management course because I was afraid I wouldn't be accepted. I opted for the latter because it also included computer science. Both the computer science and the creative side with cartography and other things appealed to me*.

I was able to learn how to work scientifically and independently right up to my Master's thesis, and the path was really well supervised.

At the HKA we had a lot of exercises; we always did a lot of practical and really applied work during the semester so that you really understood it and then the exams were no longer witchcraft.

You are still at the university - what are you doing now?

IH: I have a position as a research assistant or PhD student with Christine Preisach, I'm at the ISRG research institute and I'm helping with the SimpleAgriData project. This has nothing to do with geo, but with data science. We have a lot of data about chickens and can look at how we can make chickens' lives better.

The environmental theme seems to run through your work...

IH: I am very fond of animals and had wanted to do something with animals for my Master's thesis. I talked to Christine Preisach about it. I always thought the oceans were cool and whales in particular - I wanted to do something with them. Then I got this reality check pretty quickly, because there's not a lot of data on exactly that. I then searched and found this data set with the phytoplankton. After all, the whales need it. My aim was to somehow help protect these animals or contribute to this with my knowledge.

Thank you very much for the interview and all the best for your doctorate with us.

*HKA is continuing to develop its range of courses in a market-oriented manner, which is why the Bachelor's degree courses in Geodesy and Navigation and Environmental and Geoinformation Management will be discontinued from the winter semester 2025/26. The processing of spatial data will be further developed in the existing Bachelor's degree course in Data Science.